Reprinted under the creative commons license from Duke, N. K. & Cartwright, K. B. (2021). The science of reading progresses: Communicating advances beyond the simple view of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S25–S44. https://ila.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/rrq.411.

In classrooms, online chats, podcasts, and professional development (PD) settings, so many of us are asking: How do we translate the science of reading into daily practice? One tool that helps answer that question is The Active View of Reading. It may just change your teaching life for the better.

Why?

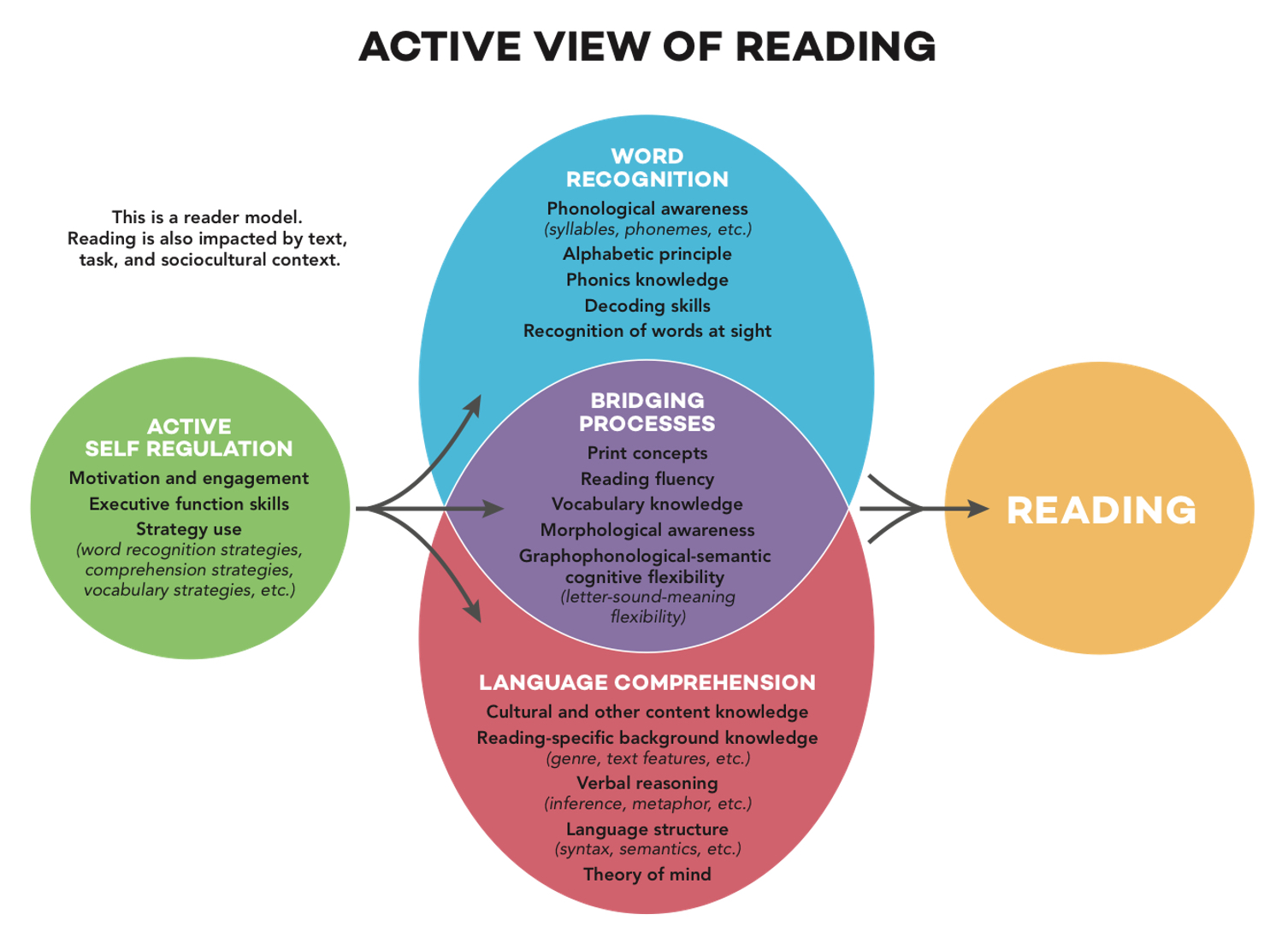

It captures the “whole” of reading, helping us to visualize a complex process. And as we discovered in our conversation for Literacy Matters, it has unusual practical power in the classroom because every single thing listed on it isn’t just research-based—each has been found to be effective in improving reading comprehension through instructional research. That is, there is nothing theoretical—all these practices have been shown to move the needle on reading comprehension.

I (Kelly) developed the model with fellow researcher Nell K. Duke to show the way readers juggle a whole bunch of skills and behaviors at once when they read. We hoped it would help teachers plan, teach, and assess reading with greater confidence and precision. And I (Leah) am a practitioner who jumped for joy when I first saw the Active View of Reading a couple of years ago, and I knew instantly that it was going to be a powerful tool when coaching teachers.

We were delighted to get the opportunity to converse because it’s all too rare that a researcher and a practitioner have a chance to get a window into each other’s professional lives. And most importantly, we were able to explore how a static, one-page graphic can become a dynamic, living document in schools. With that in mind, we share seven ideas for how to put the model into action.

1. Use it to guide professional conversation. At the start of school or any time for that matter, it’s key that leaders, teachers, paraprofessionals, and coaches are on the same page about the components of reading and that reading requires active self-regulation of interdependent processes. The goal is not ONLY to work on each component of reading separately. Rather, the goal is to work on them both separately and in conjunction with one another. I (Leah) give copies of The Active View of Reading out when I first meet teachers and refer to it in almost every professional meeting afterward. It doesn’t matter if I am doing a workshop or modeling lessons in the classroom. The Active View of Reading grounds any conversation about reading and reminds us to keep the big picture of comprehension in mind, without neglecting any components.

2. Use it to examine/reflect upon your teaching and assessing. As a literacy consultant, I (Leah) am always helping teachers reflect upon their teaching so that they can have a greater impact on their students. We can use the Active View of Reading to anchor these conversations. When I’m working with teachers, they will often notice that they have become adept at teaching students how to do a single component in the Active View of Reading, but they aren’t doing enough instruction on helping students learn to juggle more than one part of the Active View of Reading at a time like skilled readers do. For example, teachers might be working with students on fluency through the word recognition strand but not realizing how language comprehension influences fluency as well. I have them reflect upon the question: How do I shift my teaching so that I am not only instructing and assessing the parts of reading separately but also instructing and assessing how students do when trying to use more than one part at a time?

Across the year, you can have many different types of reflective conversations using the Active View of Reading as the focal point: Are there areas of The Active View of Reading you are strong in? Areas you may be overemphasizing? Areas to augment? Use the graphic to ensure that all the pieces are brought into the classroom. For example, we may talk about how a child’s culture and content knowledge influence their reading. Every child brings funds of knowledge. How good are we at knowing them, supporting them? Do the texts in our book bins, instructional plans, and the questions and themes we privilege mirror our students this year? We might also talk about how students' knowledge of vocabulary is growing/not growing across the year. All of these conversations help us to ensure that teachers are bringing all parts of the reading into their instruction and helping all students reach their full potential.

3. Use it to augment teaching and learning related to Bridging Processes. Word recognition and language comprehension processes are not entirely separate collections of skills. In fact, these skills actually overlap and influence one another during reading. Not only do readers need to manage and coordinate word recognition and language at the same time while reading (a difficult task in and of itself), there are important reading processes that actually involve aspects of both language comprehension and word recognition at the same time. Because these processes bridge word recognition and language comprehension, Nell Duke and I (Kelly) called these Bridging Processes. For example, a strong vocabulary certainly aids language comprehension, but it also improves the ability to recognize and pronounce unfamiliar words as they are being decoded, using phonics knowledge. Similarly, fluency requires students to be both accurate and automatic with decoding and word recognition, but it also requires students to attend to meaning in order to read with the proper phrasing, prosody, and expression. Fluent readers seamlessly juggle word recognition and meaning to produce reading that sounds like talking.

Likewise, morphological knowledge (knowledge of words’ smallest meaningful parts, like roots and affixes) facilitates and involves both word recognition and comprehension processes, again bridging these important skills. Skilled readers are able to flexibly shift their attention back and forth between decoding and meaning (graphophonological-semantic cognitive flexibility; GSF), but for those readers who have trouble shifting, that flexibility can be taught. The purple color in the Active View diagram reminds us that these bridging processes help readers coordinate word recognition (which is blue in the Active View diagram) and meaning (which is red).

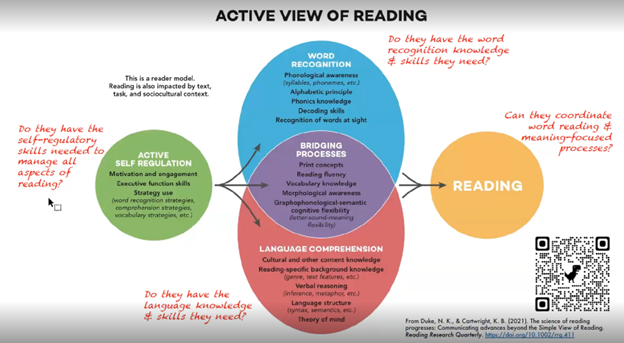

4. Use it to ask questions while looking at student data. Whether we look at formal assessments or students’ current performance at a small group reading table, we can look at the Active View Model as a kind of menu of possibilities of both skill strengths and skills in need of growth. Take a look at the questions in red on the graphic below to get you started. For example, if a reader is having trouble, ask: Which skills here does he have? Which does he not yet have? We then use this information to help us form flexible reading groups and plan instruction.

5. Use it to debrief with another teacher after a lesson. Teaching children to read is complex! We need to open our doors and invite grade-level colleagues in to help us know the impact of our instruction. For example, recently, I (Leah) modeled a lesson for teachers that had students both reading a decodable text and writing a text that focused on that month's foundational skills. Afterward, the teachers and I got together and used the Active View of Reading to confirm that the groups’ blending and segmenting were all accurate. Decoding/encoding—slow but okay. And together, the teachers and I looked at the model and were able to see that the next instruction for this group would focus on the bridging process and developing fluency by working on automaticity. This type of instruction and conversation is a great example of using the Active View of Reading to move the needle on comprehension.

6. Use it to plan units. It can help you be more precise in your learning targets. The Active View of Reading serves as a starting point for creating learning targets. For example, recently, I (Leah) was planning with a group of first-grade teachers. We were planning both the foundational skills for that month and their unit on Migration and Hibernation. We used the Active View of Reading to first come up with our learning targets for foundational skills by referring to the Word Recognition bucket. Then, we used the model to come up with our learning targets for the Migration/Hibernation Unit by referring to the Language Comprehension bucket. Finally, we used the “We-Do” Model of Writing to ensure that we were paying attention to encoding part of the foundational skills (Language Conventions) and giving students the skills and practice they needed to write clearly, coherently and interestingly (Language Composition). For both reading and writing, we made sure we planned for instruction that would help children do more than one thing at a time (bridging process in reading and application process in writing). The four different buckets that comprise The Active View of Reading and the three buckets in the “We-Do” model grounded us and helped us to translate research into high-impact instruction.

7. Use it as an assessment heuristic for readers who struggle. We are returning to the model’s use as an assessment tool because we think it’s so important teachers have support in this area. Many students struggle as they learn to read, and many teachers don’t know how to dive deeper to figure out what, precisely, is the learner’s main area of need. Broadly speaking, what we hope the Active View of Reading does is encourage teachers to look across all the collections of skills—and to appreciate that all of these components must be working in concert. The question then becomes, can the child coordinate the processes while reading? Posing this question helps us look through sharper lenses, to see the child’s performance in all of these areas.

We loved thinking, talking, and writing together about the ways that The Active View of Reading can support high-impact assessment, planning, and instruction. We hope our words empower you to integrate this model into your professional endeavors. If you do, we would love to hear how it goes. You can learn more about Leah and her work at www.leahmermelstein.com. You can also email Leah at leah@leahmermelstein.com or find her on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn and Kelly at kelly.cartwright@cnu.edu — or find Kelly on Twitter/X at @KellyBCartwrig1.