One of the greatest gifts we can give our students is the ability to read well. Decodable books are a powerful tool to build strong readers. So, what are decodable books? These books are written for beginning readers and contain specific phonics, word study skills, and high-frequency words that students have been explicitly taught. Decodable books allow students to immediately apply their letter/sound skill knowledge to connected texts. But not all decodable books are created equal. The Learning Without Tears® Phonics, Reading, and Me program offers multicriteria decodable books that feature ten exceptional characteristics to build and strengthen reading fluency for all students.

1) Aligned to a systematic scope and sequence

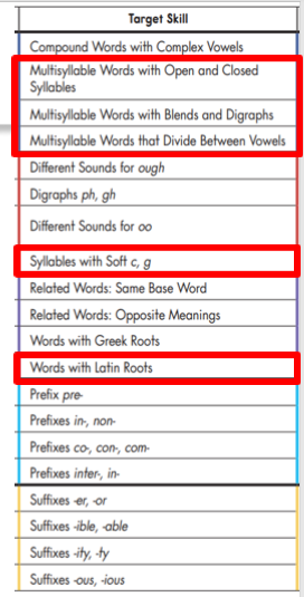

A well-developed scope and sequence is necessary to ensure that phonics and word study skills are introduced methodically over time. Start with simple skills that build upon one another and progress to more complex skills until students are proficient. The scope and sequence provides clear goals for phonics and instruction and should be aligned to decodable texts so that students have many opportunities to practice the skills they have learned. Decodable books allow students the access and practice required to obtain the desired outcome and proficiency. Phonics, Reading, and Me supplemental phonics program and decodable books are designed to teach phonics and build confidence systematically.

See Sample Phonics Scope and Sequence.

2) Targets phonics or word study skills that appear often throughout the book

To ensure that the decodable books are aligned to the scope and sequence requires a comprehensive look into the content. Make certain that the decodable books have multiple opportunities to decode and utilize the target phonics, word study skills, and high-frequency words that have been taught. For example, in the decodable book, Duck on Deck, it is evident it was written with this quality in mind. Students acquiring the target skill of digraphs ch and ck receive several opportunities to practice on these two pages alone with words such as duck, checks, and quick.

The same holds true as students’ progress in the scope and sequence and move into word study. In this decodable book from Unit D of Phonics, Reading Me: Predators; Amazing Hunters, students are given the opportunity to practice decoding words that contain the suffix er and or with words such as hunters, reporters, leader, older, teachers, and tutors.

No matter the target skill, it is important to remember that “children need to be able to practice using phonics knowledge in reading actual texts to generalize these skills” (Rupley, Blair, & Nichols, 2009; Stein, Johnson, & Gutlohn, 1999; Taylor et al., 2000).

3) Reinforces and connects to a phonics or word study skill that has been explicitly taught and provides recursive review

As we think about classroom practices, it is important to reinforce and connect to a phonics and word study skill that has been previously taught. Students do not cement new learning into their long-term memory within one or two lessons. It takes several rehearsal opportunities to make this learning sticky. It is imperative that when we introduce a new skill and purposefully infuse it into our instruction. This ensures mastery rather than just exposure. This response could be because, “research examining exposure and interaction with decodable text has shown that practicing newly learned GPCs (grapheme-phoneme correspondences) in context builds decoding skill, likely because it allows children to solidify their knowledge of them” (Saha et al., 2021). This provides a strong argument for ensuring that both the target skill is apparent within the decodable book as well as the recursive review of recently taught skills. Looking deeper into the previous examples from Phonics, Reading, and Me decodable books, you can see that these texts reinforce and connect to previously learned skills within the scope and sequence that was taught.

|

|

4) Multiple opportunities for high-frequency word practice

In addition to consistent practice of target words and skills, students should also be given many opportunities to practice high-frequency words in isolation as well as within connected text, as this leads to more fluent reading (Compton et al., 2004). Keep in mind these are words that have already been explicitly taught, as decodables should serve as a reinforcement tool to cement the learning that has already taken place. When we talk about high-frequency words, we need to consider the two categories these words belong to, regular and irregular. Regular words are phonetically decodable, such as in, at, and get. High-frequency words are sometimes referred to as sight words because students need to remember parts of words or whole words by sight. Irregular words are those that do not follow familiar decodable patterns, such as you, what, and said, sometimes called “heart words.” Even decodable words become sight words when students recognize the letters and sound automatically.

To ensure that you are providing the most effective experiences with high-frequency words, choose decodables that fit into your scope and sequence of developmentally appropriate word skills. Provide multiple opportunities to read familiar and new words to build automatic word recognition by strengthening student understanding of grapheme-phoneme correspondences. This has been intentionally done in Phonics, Reading, and Me through the explicit lessons and the at-a-glance word lists found directly on the back of each decodable book.

5) Accessible, purposeful knowledge building vocabulary

Building accessible vocabulary is vital to students throughout the literacy journey because a reader cannot fully understand the text without comprehending the meaning of the words on the page. A quality decodable book with a strong design will teach vocabulary in context through meaningful, thematic connected text. Even though the human brain is wired to speak, and oral language develops naturally, Silverman (2020) found that direct instruction in language, specifically the areas of vocabulary and syntax, can support reading comprehension. In turn, the groundwork is laid for later knowledge and decoding of more complex literacy skills. With Phonics, Reading, and Me, students are exposed to rich vocabulary throughout the decodable books. In the nonfiction decodable books, text features like diagrams, labeled images, and charts also provide contextual knowledge and reinforce vocabulary.

6) Fiction and nonfiction stories that make sense

Providing students with high-interest decodables that tell real stories not only support students in feeling successful in reading, but it also motivates them to want to read more—and more often—as success and motivation tend to influence each other positively. “Good reading leads to reading motivation, just as reading motivation leads to good reading” (Toste, 2020). This is especially true when it comes to early readers. Well-written decodable texts with universal storylines encourage automaticity and capability in reading as well as student motivation because the stories make sense, have high-interest content, and feature high levels of decodability. We can relate to this as adult readers. Experienced readers are naturally drawn toward well-written books with stories that capture our attention and motivate us to keep reading. Phonics, Reading and Me’s decodable books have consistent skill coverage written within a real storyline, thus encouraging students to continue turning the pages, leading to reading success.

7) Reinforces comprehension skills and authentic reading experiences with controlled text

While the primary purpose of decodable books is to develop phonics skills in connected texts, well-written multicriteria decodable texts can help students in multiple ways, including supporting comprehension. Phonics, Reading, and Me’s decodable books are intentionally designed to be 80 percent decodable and support students in making meaning from the texts.

8) Culturally relevant, interesting, engaging, and accessible

Books help children understand themselves, others, and their local and global communities in general. It is imperative that children who are learning to read see themselves reflected in books. Studies show that students’ reading comprehension improves when they read culturally relevant books (Christ, 2018). Phonics, Reading, and Me’s decodable texts provide multiple opportunities for all students to see themselves reflected through diverse characters and culturally authentic settings. Students are captivated by the vibrant and playful art, humor, and relatable storylines.

9) Build knowledge through connected text

Phonics, Reading and Me’s balance of fiction and nonfiction decodable texts are organized into thematic units that help children build knowledge around specific ideas and concepts—like technology or animals who live in groups. According to Cervetti and Hiebert (2019), children should have opportunities to build knowledge and vocabulary skills while they learn to read. On the back cover of each Phonics, Reading, and Me decodable book, there are skill words, high-frequency words, and knowledge-building words that teachers and families can use to help children deepen their understanding about a topic.

10) Developmentally appropriate books

Learning Without Tears is known for their developmentally appropriate curriculum and manipulatives and Phonics, Reading, and Me’s decodable books are no exception. The fiction and nonfiction texts were carefully designed to foster joyful and equitable learning to meet the needs of all learners. The topics and themes that are covered are age-appropriate, and the language, print and text-structure have been thoughtfully written to reinforce grade-level phonics and word study skills. Students who have a solid alphabet knowledge foundation and understand the alphabetic principle are ready to learn using Phonics, Reading and Me’s decodable phonics books.

If your students require stronger alphabet knowledge support, A-Z for Mat Man® and Me may be more developmentally appropriate.

References

Anderson, R.C., Hiebert. E.H., Scott, J. A., & Wilkinson. I.A.G. (1985). Becoming a nation of readers: The report of the commission on reading. Washington, DC: National Institute of Education. U.S. Department of Education.

Cervetti, G.N., Hiebert, E.H. (2018). Knowledge at the Center of English/ Language Arts Instruction. The Reading Teacher, 72(4).

Christ, T. Chiu, M.M., Rider, S., Kitson, D.; Hanser, K., McConnell, E.; Dipzinski, R. Mayernik, H. (2018). Cultural relevance and informal reading inventory performance: African-American primary and middle school students, Literacy Research and Instruction (2018).

Compton, D. L., Appleton, A. C., Hosp, M. K., (2004). Exploring the Relationship Between Text-Leveling Systems and Reading Accuracy and Fluency in Second-Grade Students Who are Average and Poor Readers. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 19, 176-184.

Rupley, W. H., Blair, T. R., & Nichols, W. D. (2009). Effective reading instruction for struggling readers: The role of direct/explicit teaching. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 25(2-3), 125–138.

Saha, N.M, Cutting L.E., Del Tufo, S., & Bailey, S. (2021). Initial validation of a measure of decoding difficulty as a unique predictor of miscues and passage reading fluency. Reading and Writing, 342(2), 497-527.

Silverman, R. D., Johnson, E., Keane, K., & Khanna, S (2020). Beyond Decoding: A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Language Comprehension Interventions on K-5 Students’ Language and Literacy Outcomes. Reading Research Quarterly, 55, S207-S233.

Stein, M., Johnson, B., & Gutlohn, L. (1999). Analyzing Beginning Reading Programs: The Relationship Between Decoding Instruction and Text. Remedial and Special Education, 20(5), 275–287.

Taylor, B. M., Anderson, R. C., Au, K. H., & Raphael, T. E. (2000). Discretion in the Translation of Research to Policy: A Case from Beginning Reading. Educational Researcher, 29(6), 16–26.

Toste, J. R., Didion, L., Peng, P., Filderman, M. J., & McClelland, A. M. (2020). A Meta-Analytic Review of the Relations Between Motivation and Reading Achievement for K–12 Students. Review of Educational Research, 90(3), 420–456.