Teaching children to read is____________. As a fill-in-the-blank exercise, we’re guessing most teachers would say hard, arduous, and overwhelming. And with more students than ever entering school with literacy skill deficits largely due to the pandemic, we understand the challenge. But one sunny forecast is this: Educators have never been as unified as now on how to teach early reading instruction. Drawing on decades of research from multiple fields, teachers, leaders, and families can come around the table and discuss a body of knowledge known as the Science of Reading.

At Learning Without Tears, we offer an array of blogs and vlogs to help educators keep current on this research and how to best apply it in the classroom. In this blog, we look at how to maximize the power of decodable texts to develop reading and writing. But first, let’s look at why decodable texts are an important part of instruction aligned to the Science of Reading.

Decodable Texts Explicitly Mirror Skill Development

If we think of the Science of Reading as a big banner in the sky, that message might read: Explicit, Systematic Instruction. Everything else—all the research-based practices in the classroom—arise from that teaching premise. This type of direct instruction develops skilled readers because it develops foundational skills that reflect how the human brain learns language. When we teach explicitly, we are transparent. We directly tell students the skill we are teaching and why it is important. When we are systematic, it means that our phonics and reading instruction purposefully builds from the simple to the complex in a way that works best for student learning (Blevins, 2017).

The framework that organizes all of this is a phonics scope and sequence. But the scope and sequence are merely the skills, right? It’s the texts and student practice that bring it all to life. When children read connected texts, they can generalize their phonics knowledge. They can begin to apply it in other reading situations. They use recently learned sound/spelling knowledge in conversation and writing too. This is where decodable texts enter in, as they are a teaching tool that helps ensure that literacy develops for each child through reading, writing, speaking, and listening related to books. Silverman (2020) found that direct instruction in language, specifically in the areas of vocabulary and syntax, can support reading comprehension.

Decodable Texts Hit Many Learning Targets

Decodable texts are written to teach phonics skills. They are sometimes called controlled texts because they stay within set boundaries of a phonics scope and sequence. They help you control the reading experience for learners, providing them with a sufficient challenge while avoiding overly advanced skills and concepts. They are decodable, meaning students can sound out a high percentage of the words because they have the appropriate phonics skills.

As a result, decodable texts give students opportunities for successful reading experiences. Children need to be able to practice using phonics knowledge in reading actual texts to generalize these skills. (Rupley, Blair, & Nichols, 2009; Stein, Johnson, & Gutlohn, 1999; Taylor et al., 2000). Children will lose confidence or disengage if the texts are too difficult.

Whether fiction or nonfiction, the decodable book provides students with concrete examples of sound spellings, high-frequency words, syntax, grade-level content, and so on. This is why decodables are considered multicriteria texts—they hit many learning targets.

Decodable texts are instructionally valuable because they align with your weekly phonics lessons. They make it easier to provide direct instruction in language, specifically the areas of vocabulary and syntax, which supports reading comprehension (Silverman, 2020).

Decodable Texts Provide Vital Reading Practice

The decodable texts you use in your instruction week to week reflect your scope and sequence, so students have opportunities to practice newly taught skills (target skills) immediately. Students practice during the lesson by listening to you read aloud, choral reading, and responding to questions you ask to build comprehension and check their developing phonics knowledge.

Then, in small groups and with partners, students can engage in follow-up activities you give them as they reread the book. This rereading is a boon to learners’ developing word knowledge and reading fluency. The instructional focus of the activity might be: blending work; or rereading and then retelling; it might be to determine something about a character or a plot point; notice punctuation; look at sentences and syntax; find the target words. From readiness skills to vocabulary to high-level comprehension, we use decodable texts to teach reading.

Decodable Texts Provide Bridges to Writing Practice

All the qualities of decodable texts that make them excellent tools for teaching reading make them excellent tools for teaching writing. And for using writing to improve reading. Researchers Steve Graham and Michael Hebert present a robust evidence base in their report from the Carnegie Corporation (2010). Citing Fitzgerald and Shanahan (2000), they make the point that reading and writing are both functional activities that can be combined to accomplish specific goals, such as learning new ideas presented in a text. Reading and writing are both communication activities, and writers should gain insight into reading by creating their own texts (Tierney and Shanahan, 1991), leading to better comprehension of texts produced by others.

Applying this research in the context of early literacy instruction, encoding—spelling/writing—is the flipside of decoding. Thus, when we ask students to respond to decodable books in writing, we help them continue to get a handle on the target phonics skills. (And deepen understanding of previously taught skills). Let’s take a tour of some examples of decodable texts and writing activities.

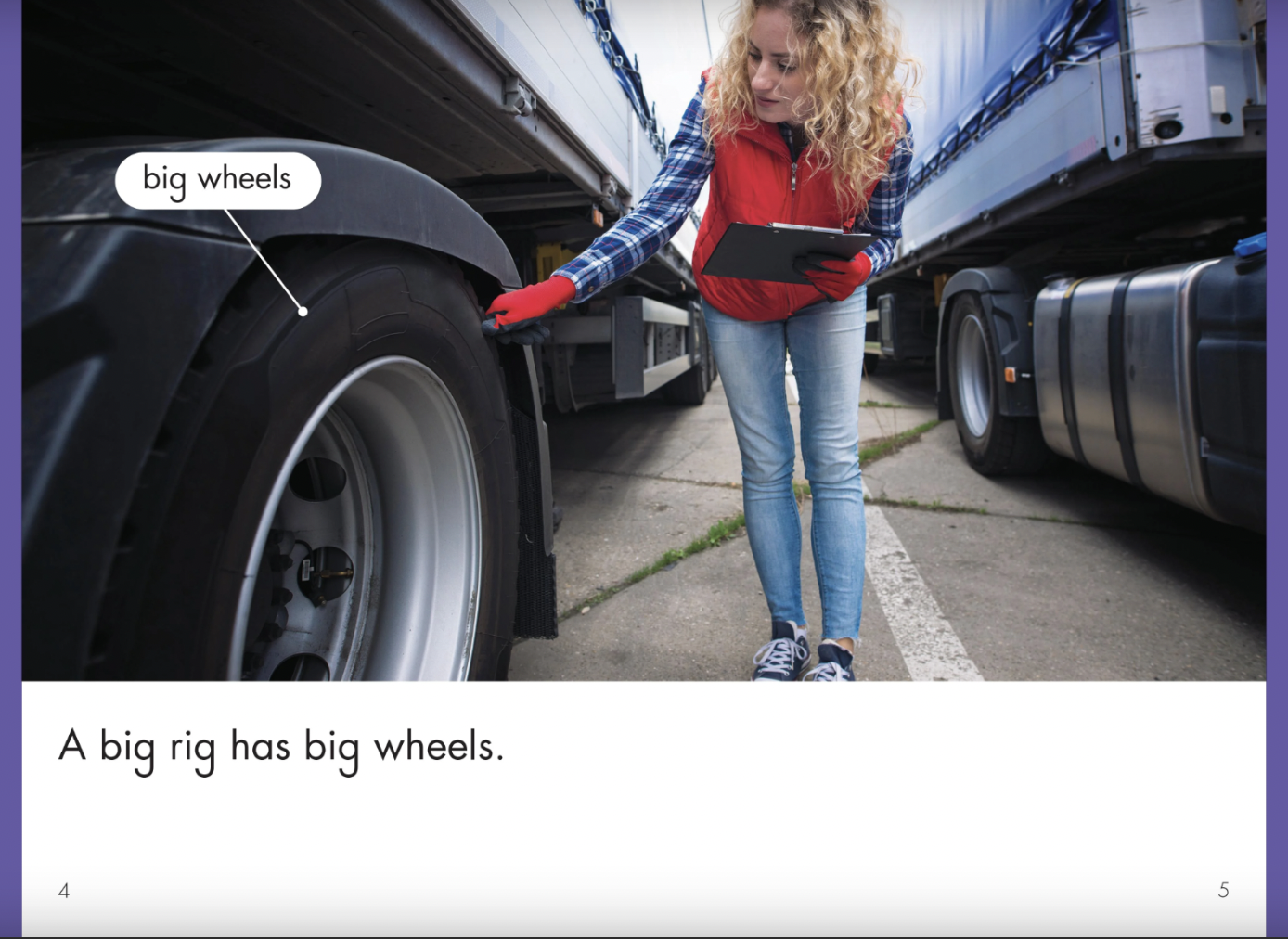

Following whole-class reading instruction, children in kindergarten can be invited to look at the book again in small groups, with your guidance or in partnerships, or during center time. To focus on a particular writing skill, you might focus on just one page or two. Using the page shown above, you might provide students with a paper with the sentence starter: Big rig has____________. Students would write “big wheels.” For an additional challenge, students who are ready to write more could be asked to reread the book and write their own additional sentences (Big rig has a cab. Big rig has lights. Big rig runs on gas, and so on.)

For teaching guidance, you can use the list of target sounds/spellings and/or words provided in these texts. Spelling, verbs, sentence structure—you can teach and assess many skills through simple writing activities. (See the partial list of skills below).

Offer Both Fiction and Nonfiction Texts and Practice

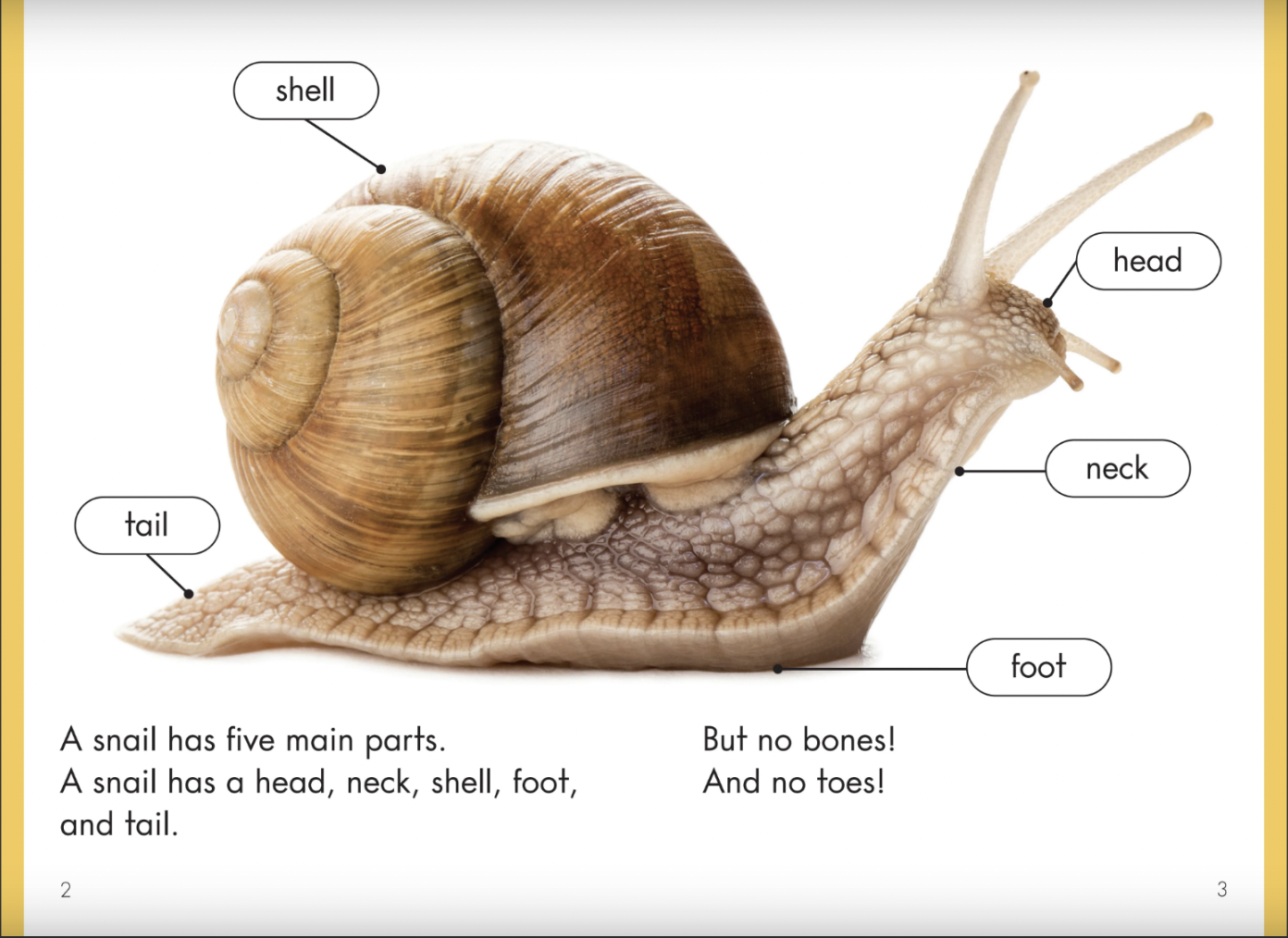

Students need—and enjoy—both fiction and nonfiction decodable texts, and each type offers opportunities for teaching spelling and writing techniques that show up in the text. Take your cues from what you see. For example, in the nonfiction book Snail Trails, written for Grade One, this page provides a strong example of using labels and pictures to share facts:

Students can reread this page to guide them to find photos or draw pictures of a chosen animal (plant, insect, or anything) and write labels for them.

You can scale up or scale down the writing activity’s complexity easily. For example, some students might work on a single image and label; other students can write several labels for images. Students can be supported with scaffolds like sentence starters, wall charts, sentence frames, whiteboards and markers, and other tools.

Skills in Focus

Use your weekly phonics plans to find your writing focus. Also, use what your assessments are showing about writing skills in need of shoring up. Along with writing ideas like those shown above or as separate activities on other days, select pages to teach:

- Spelling

- Punctuation

- Capitalization

- High-frequency words

- Connecting words

- Verbs

- Sentences

- Syntax

- Adjectives

This list is just the beginning. Refer to your curriculum for more grade-level-appropriate skills.

Knowledge-Building for Readers and Writers

Beginning in kindergarten, we use read-alouds, shared reading, and decodable texts to immerse children in ideas, imaginative stories, information, and universal human themes. The more students read, the more they expand their vocabulary and develop content knowledge. And the more students write, the more they comprehend—and can organize what they have learned.

Decodable texts provide excellent models of various text structures for students because they are carefully written for each grade level. They also provide examples of craft techniques, including repetition, lists, figurative language, and dialogue. And at a basic level, each decodable text can be used to talk about book features—titles, headings, page numbers, and so on.

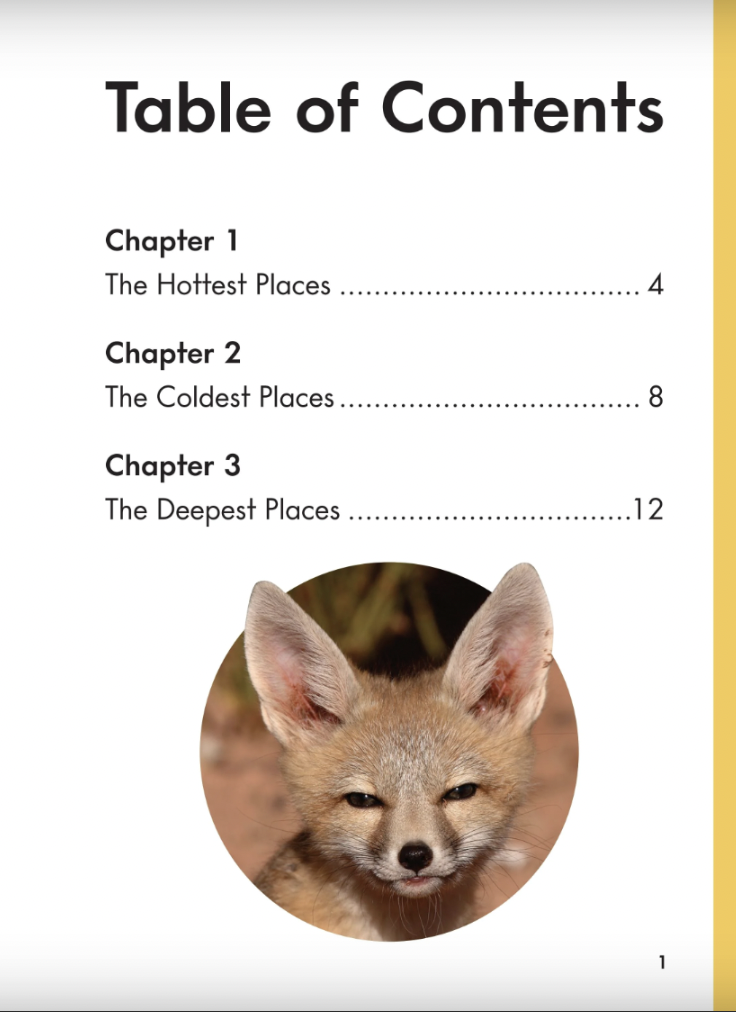

In this decodable text for Grade Two, for example, you might use the table of contents page to present a lesson that integrates reading and writing:

As a reading activity, guide students to notice that the author uses three chapters to organize the ideas. Talk about how seeing this table of contents helps us get ready for reading. Invite children to practice using the contents page to flip to various pages—e.g., Find where the information about hottest places begins. And, Can you turn to the chapter about Coldest? And so on.

After students read the book a few times with the class, later in the week, or the following week, you can return to the contents page and have students use it to support their own nonfiction mini-book about a topic they have been studying. For students who struggle with writing, the three “chapters” can be three different facts on separate pages with pictures. More advanced students can write longer sentences and/or more sentences per chapter.

Writing to Engage Readers

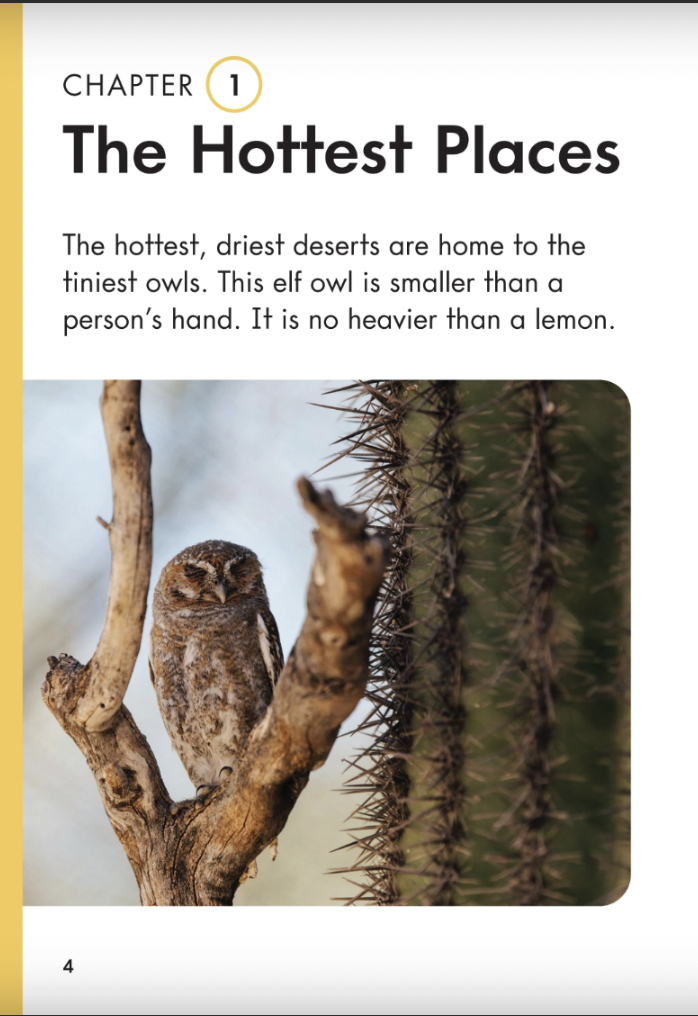

Look at your decodable texts for an eye for teaching techniques that help writers convey ideas in interesting ways. Take a look at page 4 of Hottest, Coolest, Deepest.

After you have read the book aloud and talked about it, point out the author’s use of comparison to help readers understand the owl’s size and weight:

“This elf owl is smaller than a person’s hand. It is no heavier than a lemon.”

Have students turn to a partner to share their thoughts about the comparison. How does it help them learn about this owl?

Find a few other comparisons in other decodable texts, and perhaps start a wall chart of favorites students can refer to as they write. Engage in shared writing about a familiar object, using comparisons to give the description verve. Ask students to write their own description of an object (or animal) that compares it to other things.

Developing Savvy Sentence Skills

Throughout these writing activities, students develop fluency without even knowing it. They constantly go back to the text and reread as they copy the craft technique, cementing automaticity with words and word meanings. Young readers and writers are also progressing in their capacity to comprehend sentences of greater complexity. Use decodable books to teach about sentences and how effective writers connect one sentence to the next.

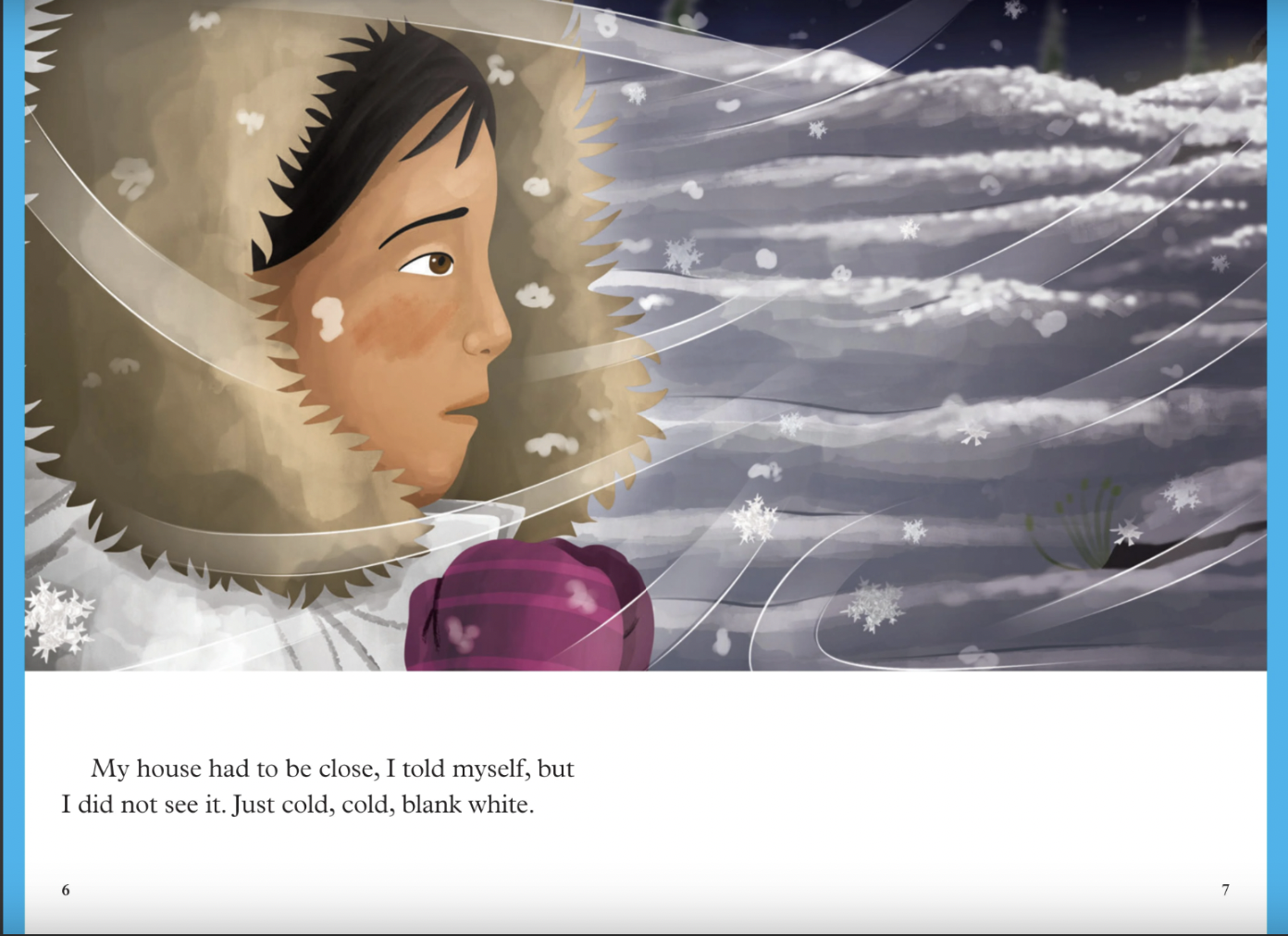

By Grade Three, students are reading and writing sentences of greater complexity. Decodable texts are ready with terrific models. Take a look at page 6 of Most of the Way Home, a fiction story.

“My house had to be close, I told myself, but I did not see it.”

This example of more sophisticated syntax can be the focus of a writing lesson, in which you would move from shared writing and discussion about it to an independent writing activity. Students learn that by setting off “I told myself” with commas, the writer can convey a character’s internal thinking. As readers, they will pay particular attention to these moments in the text, too, to infer character motivation.

One Book, Many Entry Points

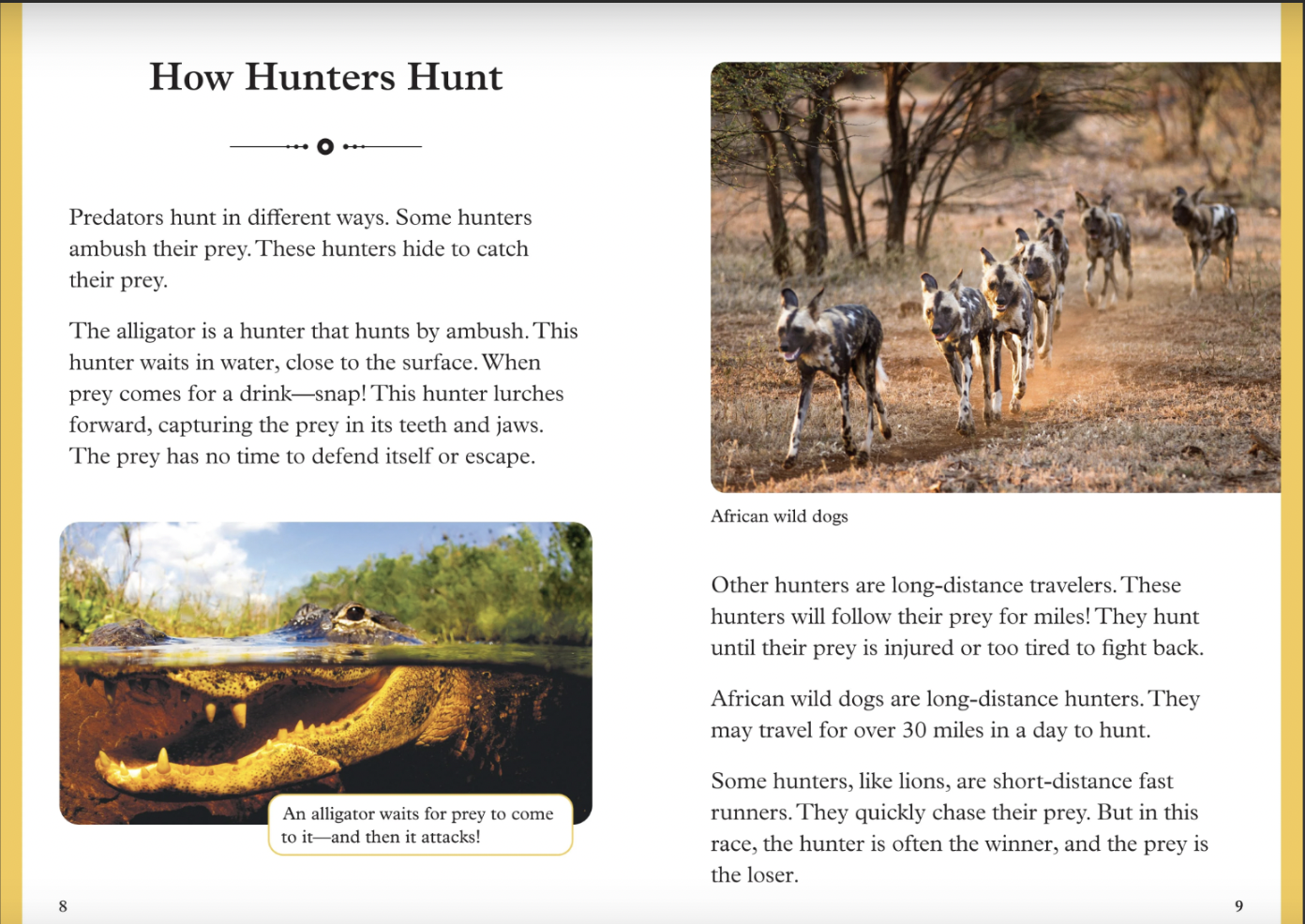

Last but not least, high-quality decodable texts have words and pictures that support comprehension. As such, there are some pages and features that are relatively easy and other pages that provide greater challenge. This range makes them powerful tools for teaching reading—and makes them easy tools to use for differentiated writing instruction. You can select different pages/features for different levels of students. For example, look at pages 8 & 9 of Predators: Amazing Hunters. As a reading lesson, it’s a great example of how readers can build understanding by noticing the way the author uses a pattern to convey information. A statement, followed by an example. Over and over for each type of hunter. We can teach readers to read each section and then pause to summarize information before reading on.

For above-grade-level readers and writers, you could use this two-page spread as a blueprint for a writing activity.

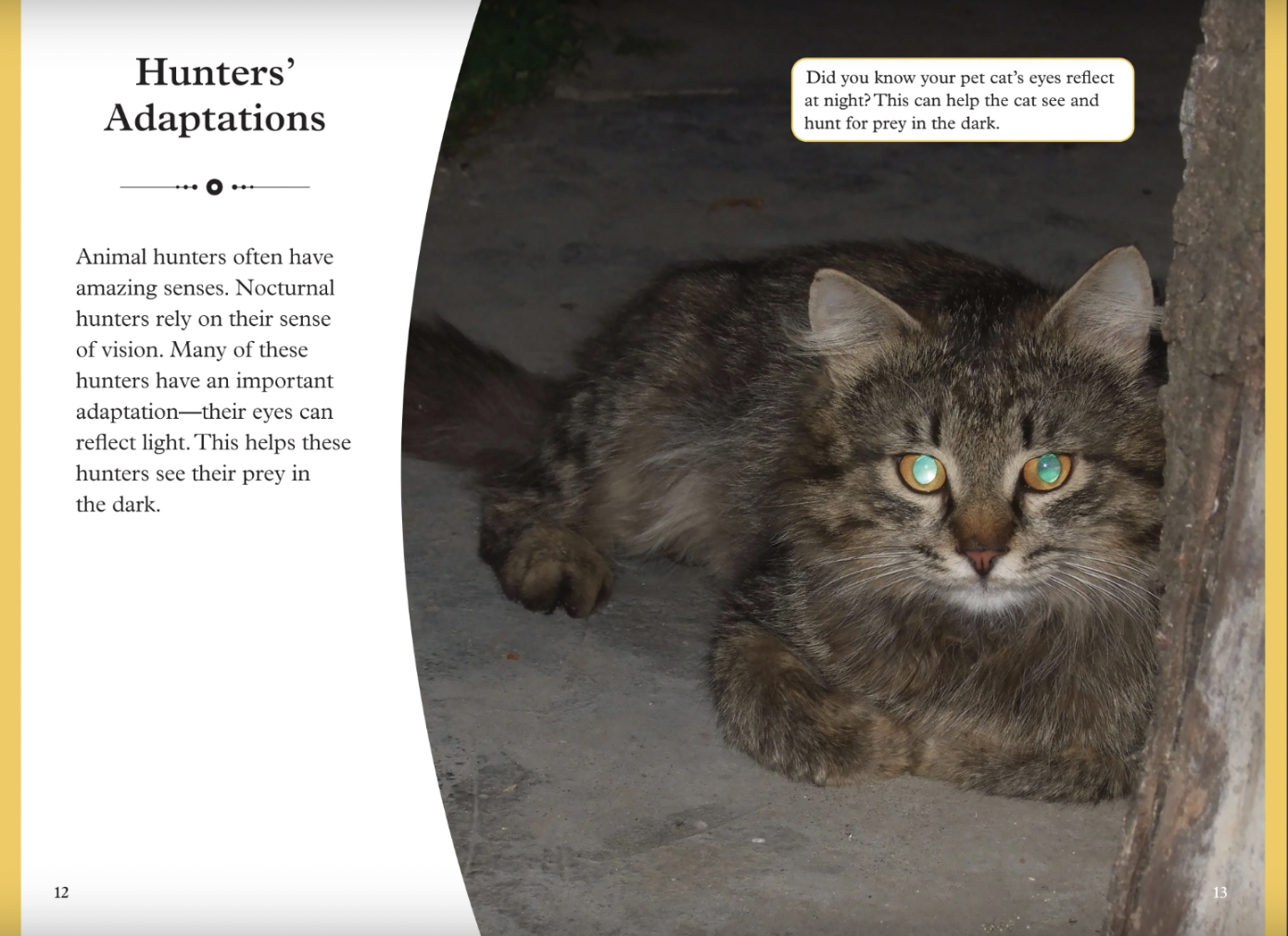

Right within this same text, just a few pages later, you can find text and image that provides a less challenging writing model.

Students who struggle with encoding can find a photo of a nonfiction topic and write a simple caption or label for it.

For decades, reading researchers and practitioners have talked about the importance of reading in learning to read. “Eyes on print” is a familiar mantra. Yet as these decodable text examples and encoding activities show, “hands on pencil” is just as important. When we use these texts to forge meaningful reading and writing connections, children’s literacy grows—as big as the sky, as sure as sunrise.

Be sure to check out 10 Qualities of Phonics, Reading, and Me Decodable Books.

References

Anderson, R.C., Hiebert. E.H., Scott, J. A., & Wilkinson. I.A.G. (1985). Becoming a nation of readers: The report of the commission on reading. Washington, DC: National Institute of Education. U.S. Department of Education.

Blevins, W. A Fresh Look at Phonics (2017). Corwin Literacy.

Compton, D. L., Appleton, A. C., Hosp, M. K., (2004). Exploring the Relationship Between Text-Leveling Systems and Reading Accuracy and Fluency in Second-Grade Students Who are Average and Poor Readers. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 19, 176-184.

Graham, S. and Hebert, M. Writing to Read: Evidence for How Writing Can Improve Reading (2010). A report from Carnegie Corporation of New York.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2000): Teaching Children to Read: An Evidence-Based Assessment of the Scientific Literature on Reading and Its Implication for Reading Instruction.

Rupley, W. H., Blair, T. R., & Nichols, W. D. (2009). Effective reading instruction for struggling readers: The role of direct/explicit teaching. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 25(2-3), 125–138.

Saha, N.M, Cutting L.E., Del Tufo, S., & Bailey, S. (2021). Initial validation of a measure of decoding difficulty as a unique predictor of miscues and passage reading fluency. Reading and Writing, 342(2), 497-527.

Silverman, R. D., Johnson, E., Keane, K., & Khanna, S (2020). Beyond Decoding: A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Language Comprehension Interventions on K-5 Students’ Language and Literacy Outcomes. Reading Research Quarterly, 55, S207-S233.

Stein, M., Johnson, B., & Gutlohn, L. (1999). Analyzing Beginning Reading Programs: The Relationship Between Decoding Instruction and Text. Remedial and Special Education, 20(5), 275–287.

Taylor, B. M., Anderson, R. C., Au, K. H., & Raphael, T. E. (2000). Discretion in the Translation of Research to Policy: A Case from Beginning Reading. Educational Researcher, 29(6), 16–26.

Toste, J. R., Didion, L., Peng, P., Filderman, M. J., & McClelland, A. M. (2020). A Meta-Analytic Review of the Relations Between Motivation and Reading Achievement for K–12 Students. Review of Educational Research, 90(3), 420–456.